FICO Credit Score Calculations are Changing

Jan. 23, 2020 7:00 am ET

By:AnnaMaria Andriotis

Changes in how the most widely used credit score in the U.S. is calculated will likely make it harder for many Americans to get loans.

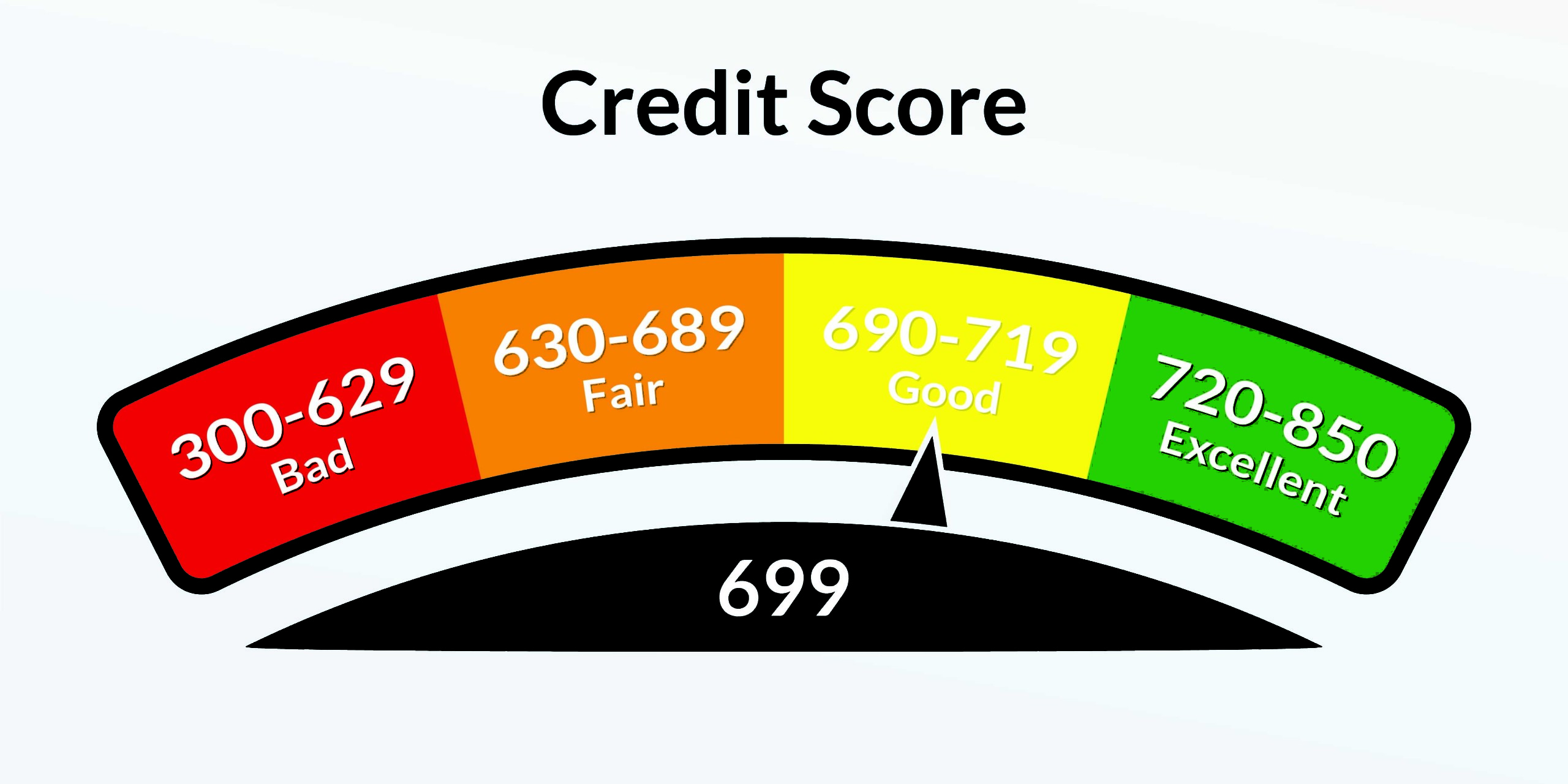

Fair Isaac Corp., creator of FICO scores, will soon start scoring consumers with rising debt levels and those who fall behind on loan payments more harshly. It will also flag certain consumers who sign up for personal loans, a category of unsecured debt that has surged in recent years. The changes will create a bigger gap between consumers deemed to be good and bad credit risks, the company says. Consumers with already-high FICO scores of about 680 or higher who continue to manage loans well will likely get a higher score than under previous FICO versions. Those with already-low scores below 600 who continue to miss payments or accumulate other black marks will experience bigger score declines than under previous models.

Millions of consumers could see their scores rise or fall as a result of the changes, the company said.

The changes are an about-face from recent years, when FICO and credit-reporting companies made changes that helped increase scores for some consumers, such as removing some negative information, including civil judgments, from credit reports.

Credit scoring and reporting companies also recently started factoring in such information as bank account balances and utilities payments to help give consumers with limited credit histories a better shot at getting loans.

Those recent moves can help revenue-hungry lenders identify more creditworthy consumers and make it easier for them to be approved for loans. Average FICO scores have been rising steadily following some of these changes and an improving economy.

The U.S. consumer borrowing industry revolves around companies such as FICO, which help lenders decide whom to lend to. Credit-reporting firms including Experian PLC, Equifax Inc. and TransUnion collect data on consumers and compile it in con sumers’ credit reports, which then determine their FICO scores.

The new FICO changes reflect a shift in U.S. lenders’ confidence in the economy, which has been expanding for more than 10 years. Consumer loan losses remain low compared with during the last recession, but consumer debts are at record highs, with many Americans forced to rely on debt to help fund their everyday lives.

Lenders in recent years had asked the credit-reporting and scoring companies to help them find more borrowers. But lenders are also trying to balance the need to expand loan volume with a rising concern about the longevity of the economic recovery and whether credit scores are making some consumers appear more creditworthy than they are.

“There are some lenders that see there are problems on the horizon in terms of consumer performance or uncertainty [about] how long this [recovery] is going to go,” said David Shellenberger, vice president of scores and predictive analytics at FICO. “We definitely are finding pockets of greater risk.”

On an earnings call last year, Capital One Financial Corp. Chief Executive Richard Fairbank warned that consumers across the industry might not be as creditworthy as their scores suggest.

Missed payments and most other negative information that would hurt a score typically roll off a report after seven years, which means lenders might not have insight into how a consumer fared during the crisis, he said.

The changes will affect new versions of the FICO scores. FICO updates its scoring model every few years to reflect changes in consumer borrowing behavior and performance. When it last announced such changes, in 2014, they were viewed as likely to help boost consumers’ credit scores.

Whether to adopt the new FICO scores will be up to lenders, which can generally decide which version of FICO to use or whether to use a competitor such as VantageScore. (There are some exceptions: For example, most lenders use a certain version of the FICO score to sell mortgages to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.) One of the new versions, called FICO 10 T, will place greater weight on recently missed payments. Consumers who fall behind or stop paying their debts are likely to see their credit scores fall more with this model. Those whose last delinquency is at least a year old could see an improvement in their scores.

The changes are meant to partly offset the effects of settlements between credit-reporting firms and states that date to 2015. Those settlements, aimed at removing erroneous information from credit reports, resulted in Equifax, Experian and TransUnion removing most tax liens and judgments from reports.

Unlike previous FICO scores, 10 T will assess how consumers’ debt levels have changed during the past two or so years. FICO scores so far have reflected consumers’ balances during roughly the most recent month tracked. This change will place more weight on rising debt levels. Consumers who previously paid their credit-card bills in full but shift to carrying growing balances for several months will likely end up with a lower score. On the other hand, consumers who tend to increase card debt during a specific month each year and then pay it off quickly will likely experience a smaller drop in their score than they currently do.

The changes will likely hurt scores even more for consumers who have a high “utilization” ratio—for example, when credit-card debt is nearly equal to a consumer’s set spending limit—for a sustained period of time.

FICO for the first time will place more weight on personal loans in a way that penalizes some borrowers. For example, consumers who transfer credit-card debt to a personal loan but continue to rack up credit-card balances will likely experience a bigger drop in their credit scores.